6: Blind Faith

WildBoots

Never underestimate seeds.

- Pronouns

- She/Her

- Partners

-

6: Blind Faith

Chris wasn't entirely surprised when he woke alone in the tent. Una's sleeping bag was neatly folded beside him; she must not have known to stuff it into its bag.

For a moment, he lay listening to the woods waking up, and among the waves lapping the shore and pokemon calls, he picked out the dinging of a spoon against a pan. He unzipped the door on his side of the tent and leaned out to see Una sitting beside the campfire, stirring something in Chris's little fold-up saucepan.

"Oh. Hi," he said.

"Good morning."

With an awkward wave, Chris zipped himself back inside the tent to change into his hiking clothes. His belt snagged as he pulled it through the loops. He yanked—and cursed when he felt something snap.

"Are you unwell?" Una called.

"I just did something dumb." He emerged from the tent, pulling taut the torn belt loop to show where it had come unattached. "Only two left."

There was a trainer joke that you could tell the number of badges someone had by the number of belt loops they'd ripped. Maybe joke wasn't the right word.

Chris had known for some time that his backpack was chafing the ones along the back and there was wear from the wide and weighty belt itself, but he'd hoped to be able to hold out a little longer before having to go in for repairs.

He couldn't help being hard on his clothes. Across all the miles with bulky cold-weather layers, supplies for all his pokemon, a tent, and cookware—there was no room to pack extra. He'd been wearing the same pair of pants when he first left Olivine and had already had them repaired three times times. One patch was from the time he scraped his knee running from a wild tauros. One was from the time he washed them in a run-down hostel washing machine only to find them full of holes when the cycle finished.

Repairs weren't cheap. The material was tricky to work with, so said the tailor, but Chris suspected they upcharged trainers because they knew they could. A person who only owns one pair of pants is often in the position of making desperate decisions.

Una said, "If you have a needle and thread, I could easily repair it."

He shook his head. "I don't. But thanks."

Una watched him zip the tent flap behind him. "Is it not possible to purchase another pair?"

If he had fifty extra dollars in his pocket from the battle yesterday, it would be easy. But he only said, "It's okay. I'll figure it out."

He joined Una by the fire, threading his belt through the remaining loops. "Looks like you got the hang of the matches."

She smiled, blushing. "I expended several in the attempt. I apologize."

"That's okay. Kosho usually lights the fires anyway." He took in the sugary smell rising off the pot. "Did you make breakfast?"

The previous evening, Una had been flummoxed by the magic trick of turning a packet of RediMeal powder into curry by adding water. Apparently, she had adapted quickly.

"And tea." She pointed out the cup at his feet.

"Wow," he said, holding the cup close and inhaling the steam. "No one has made me breakfast since before I left home. Thanks."

Una served them each a portion of instant oatmeal from the pot. "I was awake."

Chris stirred. "Are there strawberries in here? Where did these come from?"

"Growing beside the path. You did not notice them yesterday?"

"No, I didn't. I'm glad you did though."

Birdsong and the smell of pine filled the air. The sky was clear. In the light of day, the lake looked flat as paper.

"Last night," he said. "The lake …. It feels like a dream."

Una laughed sharply. "Everything I have seen in recent days has been like a dream."

Chris bit the inside of his cheek and said nothing. He wondered, yet again, what he was doing running in circles with a near stranger. But where else was he supposed to tell her to go?

Brow furrowed, she stared across the lake. "I do not know what to feel. Never have I seen a god in the flesh before—and never did I dream that I might. It was not what I imagined."

"I didn't even think they were real," he admitted.

Dad had taught him better.

As a child, Chris cried in terror of the ocean, certain the Whirl Islands monster would drag him under. Mom would've let him cling to her forever, face buried in her shoulder, but Dad had pried him loose and spun him to face the water.

You can't get worked up over stories, he'd said. The only only things you need to worry about on this beach are ones you can see with your own eyes.

He showed Chris how to spot rip currents and tentacool from the shore, which clouds meant thunderstorms. Be smart, pay attention, and nothing will hurt you.

Dad hadn't prepared him for when his eyes showed him something that wasn't supposed to exist. Again, he tried to reconcile Dad's lessons with Suicune's words, and again he hit a wall. It just didn't make sense.

If Una was offended by Chris's admission of faithlessness, she didn't show it. "In Ecruteak—before, I should say—some kinds of faith came easier than others. How could I doubt in Ho-oh when I can watch her shadow overhead, when I can hold one of Her feathers?"

As she lifted a hand to her necklace, he made the connection for the first time: did she mean that feather around her neck was plucked from an actual god? Before, he would've said that was impossible. Now … could he really be sure?

"But to understand her blessings, to hold her favor …. Those are much harder. Some priests spend the entirety of their vocation interpreting the remains of the burnt offerings atop Morning Tower. I suppose they did not foresee what would become of Ecruteak." Una flashed a wry smile. "And yet now is when the gods choose to speak directly. They have even given you a personal blessing."

There was a bitter edge to her voice. She wanted it to have been her.

Chris fidgeted. "Some blessing …. Kinda scary. Like that ashes on the wind stuff."

"Sometimes the gifts of the gods are fearsome."

Burnt offering Una had said. Of what, Chris started to wonder, but decided he didn't actually want to know. His skin prickled.

After a moment Una spoke again. "I have been considering what you said yesterday, how the wild is where you feel you belong. I think I feel that way as well. All my life, Ecruteak and its two towers were the center of meaning, but the gods reside there no longer. They are here." She made a sweeping arm gesture, then shrugged and tucked her hands in her lap.

Chris spoke slowly. "So you don't want to stay in Mahogany."

"No." She laughed humorlessly. "If all of your cities are like what I saw of Ecruteak and Mahogany, then I am suited for none of them. This is not my world anymore. But the trees are yet unchanged. The mountains are unchanged. I understand those things."

Chris carefully set down his bowl and leaned forward, elbows on knees. "You know, the battle yesterday—that's not a one-time thing."

And that wasn't even a bad one, he added silently.

She looked at her feet but nodded.

"I can't keep throwing battles because they upset you. For one thing, I need to pay for supplies." He toyed with a loose-hanging belt loop. "And even if I didn't ... this is what I'm out here to do."

"I understand. Or, rather, I do not and cannot understand, but …." Una met his gaze. "I know what we witnessed here last night. If you have the blessing of the gods … there must be something I am not seeing. Perhaps there is something I am meant to learn from you."

He looked away. Her gaze was too heavy.

At the same time, his heart twisted remembering how at the ruins of the burnt tower she'd hugged that carved pillar like a dying loved one. He tried to imagine waking up one morning to find everyone he knew—Mom, his high school friends, the grocery store clerk—gone. Every pokecenter computer and his Bitflex and pokeballs all defunct relics. He couldn't picture it.

What would Dad do?

Una was looking at him, waiting.

Chris managed half a smile. "I guess you could teach me how to find wild strawberries."

"Verily, I can."

"No one else would believe me if I told them what we saw last night."

"And I would be called a heretic." Una became briefly wistful before suddenly dissolving into the desperate giggling of the overwhelmed. Chris chuckled nervously until, counting off each impossible, ridiculous thing that had happened this week, he let the hysteria sweep him along too.

Finally, when the laughter had wrung him out, Chris steadied himself with a deep breath and said, "We should get going. I'll show you how to pack up the tent."

—

Maybe, Chris hoped, they would run into another trainer on the path and he could try again to make back a little cash. What they saw instead were more plants than he'd realized had names.

The Johto wilderness was beautiful, of course, when he slowed down long enough to notice. More often, however, he only thought of the undergrowth as a place where pokemon might hide or an obstacle to push past. Beyond that, he hadn't given much thought to what grew alongside the trails.

But as Una knelt and pointed, individual flowers and vines sprang out of the tangled green as if conjured by magic, and she knew a use for every single one. Waybread for bug bites and small scrapes. Yarrow for wound care and indigestion. Jewelweed for poison ivy stings.

After she pointed out the first strawberry plant, Chris easily spotted another. And another. They ate the wild berries hand-over-hand as they walked. Mojimoji didn't need them to point out berry plants to her, but all the same, the sandslash happily accepted strawberries from their hands, sweeping her long tongue over their red-stained palms.

Though it was Chris's third time passing through Route 42 , he felt as if he were seeing it for the first time.

When they crested the hill and saw Mahogany Town tucked in the mossy shadows between Mt. Mortar and the Dragon's Spine, close enough to pick out individual buildings, Chris let out a sigh of relief. They were making good time.

They walked without speaking until they had nearly come to the first buildings. "Last chance," he said with a nervous smile, knowing what her answer would be.

She shook her head but smiled. "I am content to continue."

"Just making sure."

How different she seemed already from who she'd been when they'd set out together from Mahogany Town. She left as a blank slate, a girl without a name. Now she had an air of resolve. Her gaze was sharper, her head higher.

Chris and Una walked side by side down the wide main road, soon passing the gym and The Indigo Chateau. The streets were quiet. They saw a few children playing kick the can, a pair of women carrying baskets of freshly washed clothes back from the lakeshore, and an old man smoking a pipe on his front steps. Chris slowed as they passed the repair shop.

"Will you seek a seamstress?"

He imagined sitting around the repair shop in his sleeping clothes, waiting to get his pants back. He could read his book, he supposed, or write a letter home, while outside the daylight would slowly wane.

Directly ahead, the mountains loomed green and sharp. They were so close now.

"I'll do it in Blackthorn," he said.

"Then what comes next?"

Chris took a deep breath. He pushed down thoughts of money and lost time and all the miles left to go, touching Kosho's pokeball for luck. "We're gonna climb the Ice Pass. And then I'm going to meet Clair and show her what my team and I can do."

Una tied back her long curls and wiped the sweat from the back of her neck. "Lead the way."

—

She was the first to notice the carol of delibird. As Chris passed her the bag of trail mix, she grabbed his arm and pointed, smiling mischievously.

Chris counted three of them in the tree across the way. Four. Now six. Of course they'd waited until lunch to make their appearance.

He made a noise of exasperation, reaching for Zip's ball. "Yeah, the pokemon up here aren't afraid of people at all. Persistent too."

"Oh, please—"

But Una was too slow. Zip chased the delibird out of the tree and into the sky, shooting sparks with each joyful bark.

"Don't worry," Chris said, brushing a fallen feather off of his sleeve. "They won't go far."

Sure enough, the sound of delibird hoots and trills remained constant as they finished their apples and continued up the canyon.

Alone, Chris would've been annoyed by them. But it was hard to begrudge Una her wide-eyed delight. "I guess you haven't seen a delibird before, huh?"

"Never."

Chris felt a pang thinking of how much of the world, or even just the Johto region, she'd never had a chance to learn anything about. He had grown up watching sailors on the docks, the Unovans with their gurdurrs and simipour, the floatzel and gastrodon from Sinnoh, and all manner of trainers and their pokemon came through the gym. What he couldn't see in Olivine he could easily search for in the pokedex or watch in a high-def nature documentary. He got the impression that Una's Ecruteak must have been very isolated.

Then again, if she was able to find joy in a delibird when he couldn't, maybe she was one who should feel sorry for him.

"They give humans little presents sometimes," he told her. "You know, berries, rocks … trash."

"Then they are messengers! We should leave them something too."

Chris didn't reply, glad she was walking behind him and couldn't see his face. The last thing he wanted was to encourage them.

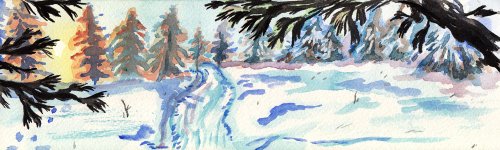

They climbed steadily, single-file. Zip darted from the head of the line and back, even shooting between Chris's feet once or twice, chasing any delibird that came too close. They hadn't reached the snow line yet—probably wouldn't until tomorrow at their current rate—but they hiked past hummocks hanging with muddy icicles, and the leafy trees phased out in favor of pines and woody shrubs dotted with red berries.

After a while, Chris piped up, "What are you humming?"

"Oh!" He heard her stumble in surprise. "I apologize. I had not realized that I was."

"It's okay. I thought it was nice." He glanced at her over his shoulder, and they exchanged shy smiles.

"It is only a silly little song."

"You can keep going. I mean, if you want to."

For a few moments, there was only the sound of their footsteps and the rustling of branches. Then Una began to sing in a thin but pretty voice.

Little bird, little bird

Fly for me high above

And carry, oh carry

This letter to my love

Little bird, little bird

O'er the many miles you sing

Do not tarry, oh tarry

You fly on borrowed wings

Little bird, little bird

Oh how far you have flown

Do not worry, oh worry

The gods will take you home

When she finished she added, "I believe there is more, but I do not recall the words. Suki, my sister, had a much better memory for songs."

"I like that. It's sweet," said Chris. "There's something almost sad about it too."

"It comes from an old story," she said. They were each getting better at masking their shock at what the other didn't know. "A young girl wins the friendship of a pidgey and the promise of a favor. Out of love for her, it agrees to carry a message to her lover on the opposite side of a treacherous mountain. The little bird delivers the letter, only to die of exhaustion shortly after."

"Oof." Unbidden, the image of the prescription pill jar brought to him by a delibird came to his mind again. "That's a lot for a little bird to carry."

"So it goes." He could hear the sad smile in her voice. "But in honor of its loyalty and fortitude, it is guided home to live among the gods."

"I guess that's something."

Nearby a delibird honked in protest as Zip rushed at it. Scree and sticks clattered down the hill as they walked.

"I like the song though."

Una hesitated for only a moment. "I know a few others. If you like."

"Yeah, sure. I'd like to hear them."

They hiked more slowly than Chris would've alone, but the time seemed to pass more quickly all the same.

—

The next day, another of Chris's belt loops tore free as they walked. He felt it go, only just managing to catch the sagging end of his belt before his pokeballs went tumbling. There wasn't enough support left for it to hold up.

Una looked back to see him frozen in the middle of the path. "What happened?"

"It broke," he said, unbuckling his belt.

Chris allowed himself a moment to stare down at the belt in his hands and feel sorry for himself. Then he slid out of his backpack and began packing everything away.

He clipped Zip's pokeball to the shoulder strap and with a carabiner, the rest he tucked into an outside pocket. He hated tying his team down to his backpack, and he felt naked without his belt. The only positive, he supposed, was that in the mountains there were few if any other trainers who might try to get into his backpack to steal his … everything.

The only way out is through.

He took a breath, shouldered his pack, and lifted his chin. "Let's keep going."

Chris made a point to turn his Bitflex to the underside of his wrist so he couldn't see the date and time so easily. A branch snagged his hood, but he shoved it aside. Then there was a smack and a cry of surprise as it struck Una behind him. He turned to see her holding a gloved hand to her cheek.

"I'm sorry! Are you okay? I'm not used to having to watch out for someone behind me. Sorry."

"I am not harmed. All is forgiven."

They spent the morning hiking in the shadow of the canyon, with a brief interlude in the sunlight around lunchtime before the sun dropped behind the high limestone walls again. It began to snow.

"So this is where you found me?" Una asked, a mix of awe and horror in her voice.

"Yeah, more or less. I don't know if it was here exactly, but somewhere near here."

He snuck a glance back in time to see her shiver. "I wonder if I will ever know how I came to be here."

Ahead, a massive fallen log cut across their path. Chris found a foothold and hoisted himself over. Then, leaning against the other side, he watched Una approach the log and falter. She was out of breath. He didn't want to, but they would have to stop and rest soon.

"Who would have thought," Una said, panting, "that I would return here so soon."

Chris dusted the snow from his gloves and reached down to offer her a hand up.

She flashed a smile, straining with forced cheer, and fumbled for a handhold on the log. But she accepted his hand and let him pull her up and over, her boots slipping. When she had both feet safely planted on the other side, she slumped against the log next to him and sighed.

He felt a surge of pride looking at her, face red with cold, a few stray curls poking out from under her knit cap. This wasn't easy for her. But she was stubborn, and he had to admire that he still had yet to hear her complain once.

"I never would've thought you'd do so well out here. Most people … wouldn't. You've got a real spark."

Inwardly, Chris flinched. It was something Dad said to gym challengers, unnatural in his own mouth.

Una answered with a breathless laugh. "This is the first thing in my life I have chosen freely and fully."

Chris didn't know what else to say so he smiled. "Let's take a break at the top of this hill. I'm feeling kinda tired." He slowed to Una's pace and they wound their way up the hill side by side.

They were nearly at the top of the hill when they heard a shrill bark, a different sound than the one Zip normally made when he was chasing a delibird.

"Zip, come here!"

There was a resounding stillness. He hadn't noticed until now how even the delibird had quieted.

"Zip?"

At the top of the hill, the path leveled out for a stretch. Zip's paw prints were easy to pick out in the snow, the shape warped by his SmartResin paw protectors. The tracks meandered to the right, and then vanished under a long, muddy skid mark—and Chris's blood froze.

In the same instant, he spotted both the muddy yellow lump of his jolteon in the snow and hunched above him, all shoulder and chest and rippling fur, not an ursaring but a full-blown ursaluna.

He had never heard of a wild ursaluna in Johto—too dry, too warm. Had it emerged from some hidden cave when the mud thawed? Or had a careless trainer assumed this was the place to release it?

A sound overhead pulled his gaze to the treetops, where two golden-faced tediursa cubs peered down at them. That was bad. There was never a good time to cross paths with an ursaluna, but especially not when she was with cubs.

Chris tried to motion for Una to stay back, but she was already right behind him. He heard her breath catch as she slid to a stop next to him.

The ursaluna sniffed the air and spun around, locking her beady eyes on Una. She snorted a puff of steam and then bellowed.

Pokemon bolted from the nearby bushes in a crunching of leaves.

Chris slowly took a step back. In a low, gentle tone he said, "Hey, easy. We're not gonna hurt your cubs."

Kosho might be big enough to scare her off without a fight. He slid his backpack off one shoulder, reaching toward the outside pocket.

That was a mistake.

The ursaluna snapped her head toward Chris and snarled. Faster than he would've believed, she dropped to all fours and rushed them. She shouldered through the bushes, stirring up snow in her wake, and hurtled toward them with her mouth open in a roar.

If he was fast—

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Una lace her hands behind her head and drop to her knees.

"What are—?"

"Chris, get down."

He hesitated for a fraction of a second, and that was all it took. Suddenly the ursaluna was only a yard away.

His mind went utterly blank, like a candle blowing out. He surrendered and put his hands behind his head. Beside him, Una lay face down in the snow, and he followed suit, closing his eyes.

Overhead, the ursaluna slewed into a stop less than a foot from Chris's head and howled her rage, spraying him with snow and spittle. For a moment she only swayed over him, but he could feel the weight and power of her even with his eyes closed. She roared again.

Chris's ears rang. He held as still as he could, but his trembling was beyond his control.

She swiped at him once, twice, knocking his pack aside with a thud. He heard fabric rip and flinched. But no more blows came. Her breath lingered hotly on the back of his neck. And then he heard heavy footfalls in the snow, and the towering shadow receded.

He waited as long as he could stand it before slowly lifting his head.

Several yards away, the ursaluna stopped and huffed at them, breath steaming. Without taking her eyes off Chris and Una, she shambled over to the tree where her cubs perched. She made call that shook the trees, and the cubs began to clamber down one at a time. They fell over themselves as they landed and then pulled themselves from the snow, gamboling in triumphant circles. It would have been cute if not for the ursaluna's continuous growls.

Rumbling, she herded them across the path towards the opposite slope. She paused one last time in the middle of the path to glower at Chris and Una, and then the three bear pokemon lumbered into the trees.

Chris and Una lay listening to the wind in the branches and distant pokemon calls for a long time before they dared rise to kneel on the cold, wet ground. Chris's heart was still pounding.

He turned to look at Una. Pine needles and snow clung to her hair, but she hardly even seemed rattled. "How did you know that would work?"

"There are many things I do not know or understand." She stood and offered a hand to Chris, smiling. "Fortunately, I do know some things about making peace with wild creatures."

—

By the fire that night, after they'd cleared away their dishes, Chris rubbed a chemical-smelling salve into the pads of Zip's paws. Then he got to work patching over the claw marks on his backpack and the back of his coat with duct tape, a holdover until they reached Blackthorn. The line of repairs was starting to seem endless.

Kosho, his coat freshly brushed, rested his chin on the fire ring and watched with half-lidded eyes. Chris couldn't begin to guess what he was thinking about, but his presence was a comfort.

The sky was pearlescent with clouds. Every so often a snatch of starry oblivion peeked through, but Chris couldn't pick out any of the familiar constellations or the new ones Una had pointed out to him.

At the previous night's campfire, Chris had showed Una the handful of tracks stored on his Bitflex, a trade for the songs she'd shared with him. She had smiled politely through the rock ballads, more curious about the recorded voices than about the songs themselves. Fair enough: Chris wasn't even sure he liked them.

He'd downloaded the tracks that made him think of his early days at the Olivine gym, wheedling for the gym trainers to teach him drills to run with Kosho, then a cyndaquil. The music reminded him of reaching for something. It poked a hole in a dark night and made the fire a little brighter.

Tonight, though, he and Una sat in silence.

"I sense the weight of your thoughts, Chris. What is on your mind?"

"It's just …." He leaned back and let Zip nestle into his half-open coat. "For a while now, most of my journey really, I've only had myself to rely on. I'm proud of that. But … if it had only been me and my pokemon out there today, I would've been in trouble."

She hummed a sympathetic sound. Heartened, he charged onward.

"It's funny. People think training is about giving commands and planning out strategies, but that's not all of it. I was thinking today about the Ecruteak Gym—you know, with the trap doors."

He'd done his best to explain the Indigo League and the gyms while they walked, but it wasn't easy when she was missing so much context, and he'd realized he didn't actually know some of the history either. Their pool of shared knowledge was widening, but slowly.

"Kosho was trying to let me know to stop, but I second-guessed him. So I fell through. If I would've listened, that wouldn't have happened.

"I almost had another one of those moments back there with the ursaluna." Even with the heat of the fire on his face, he could feel his cheeks grow hotter still. "I'm glad I listened to you. I'm glad you're here."

Una tipped her head to one side. "You have chosen a dangerous journey. Why do you continue, even knowing its risks?"

He let out a long sigh. "That's a big question. I mean, it's a lot of things, right?" He watched the flames, rubbing Zip's ear, but he could still feel Una's eyes on him. "I probably haven't been doing a good job lately of showing it, but it's fun too. I get to hang out with pokemon and hike all day and win battles. And … and I guess, probably it's because of my dad."

She waited.

"He used to be the Olivine gym leader—I don't know if I already told you that. So I've been around pokemon all my life. Kosho was bred from one of his pokemon, actually."

In a flash, he remembered Dad scolding him for feeding his cyndaquil scraps under the table, as he was in the habit of doing with his friends' pets. At the time, Chris hadn't realized yet that Kosho had been given as a pet in name only, for legal reasons. He was always intended to be a fighter. His starter. But Dad had always known their potential.

"I guess," Chris said, "I want to do things that would've made him proud. I want everyone to be able to see that I'm his kid."

"Oh. I see," said Una. "Did he ...?"

"Yeah." He cleared his throat. "But it was three years ago."

Chris shifted in his seat, prompting Zip to leap off his lap and cozy up with Kosho instead. Without a pokemon pressed against him, the cold crept back in, and he zipped his coat to his chin and wrapped his arms tight around himself.

"You learn to get used to it. I think it was harder for my mom."

After all, Chris had escaped, traded the unnatural silence of the empty house for the comforting quiet of the woods. Mom was alone in that house now.

"I think understand," Una said. "When Suki passed, many others had fallen ill with the same fever, and there was too much work to be done to spend much time in mourning."

Chris stole a glance at her. She sat with her arms wrapped around her knees, her hair partly obscuring her face.

"I'm sorry for your loss," he told her.

"As you said, one adjusts." She cracked a crooked smile. "Besides, it happened over five hundred years ago."

"Still," he spluttered. "That's hard. You're allowed to be upset about things like that. I mean, I almost didn't become a trainer because of what happened."

She tucked her hair behind her ears. "What do you mean?"

"Well, he was killed by a pokemon."

Una reached up reflexively to touch her feather necklace. "One that he was ... training?"

"No," Chris said, more defensively than he'd meant. "Definitely not. It was a challenger, at the gym. An accident."

"An accident?"

"It was this young guy who didn't really know what he was doing." He might've been younger than Chris was now, just someone trying to make a name for himself the only way he knew.

A lump rose in Chris's throat.

"We could discuss something else if you would prefer. I do not wish to upset you."

"It's fine. I don't mind."

She leaned her chin on her knees and waited.

Chris stared into the sky and spoke in a matter-of-fact tone. "The other trainer brought out a newly caught rhydon, and he wasn't ready to handle it."

When Chris had made the decision to take on the Indigo League, he'd looked up the footage. He should watch it, he thought, because he wanted to be sure he would never be that trainer.

The rhydon had been a behemoth, back crusted with lichen and moss, a creature no one ever should have tried to remove from the wild. At first it wouldn't fight at all, hunkered down, turning its armored back into hit after hit. Then, without warning—

"It freaked out. Pokemon do that sometimes their first time in a gym. It's the confined space, the lights, the crowd. The guy had no control over it, but he let it rampage anyway because he thought he might win that way."

The tape had caught the moment when the trainer's smile fell as the rhydon pivoted from Dad's fallen magmar toward the next target: the stands. The crowd scattered, leaving the rhyhorn to crash through the bleachers and into the wall. With plastic and rebar tangled around its feet, it smashed its head into the concrete again and again.

"I think," Chris said with a dry swallow, "it was just trying to escape. But when it finally burst through the wall, half of the ceiling fell."

He knew the rest from the official reports: three other trainers and an off-duty cop had finally brought the rhydon down, but the damage had already been done. Although most people had been safely evacuated from the gym, several were wounded and four were killed.

"We like to think that just because you have a pokemon, nothing can touch you, but …."

When paramedics eventually found Hiro Nakano in the rubble, there were signs his pokemon had tried to protect him … and failed.

Chris wished he didn't know that Dad's typhlosion and houndoom had been crushed beside him beneath the falling travertine. Several of his pokeballs had also broken apart in the collapse, and it took the local sheriff's office two days to recapture his loose pokemon. His charizard had never been found.

Eventually, the city had rebuilt the gym and found a new gym leader. She'd liked the exposed steel beams when she visited during the construction, and so it had stayed that way. They'd added black tile flooring that reflected your own face back at you and, most importantly, a heavily reinforced steel ceiling dome.

"And yet," Una said, "here you are."

"Here I am."

"You are fulfilling your father's wishes."

"Yeah. I think so." He felt Una's eyes steady on him, but he kept his gaze on the fire.

"And your mother? What does she want you for you?"

Chris prickled at what he took for accusation under the surface of that question. But when he turned to look at Una again, he only saw curiosity and confusion in her face.

Her parents had decided her life for her, he reminded himself. She hadn't gotten to choose. Not what had come before, and not even her arrival here, to this time. Trainer culture was the least of the gaps between the two of them.

He thought for a minute. "Mom was angry at first when I told her I'd decided to train, but she wouldn't say so. I mean, she's supportive, but she doesn't really understand it. Sometimes I don't either, honestly. It's just something I have to do."

Chelsea Lange had never taken her husband's name and never learned to love his profession. Hiro used to tease her. You must be the only nurse in the entire world who covers her eyes at the sight of blood.

Listen, she would say, poking him in the shoulder or the ribs or whatever she could reach, it's not all blood. Just because I can take a blood sample doesn't mean I like watching two pokemon knock the stuffing out of each other.

But she'd gone to his matches anyway, all the important ones. Chris sat in the audience next to her, and his job was to tell her when it was safe to look again if it took an ugly turn. And he'd known from day one that she would come to his matches too.

She'd already done a lot to support his training. Studying for his licensing exam hadn't been too bad—the test was mostly common sense questions, and by then he'd been doing only enough in his regular classes to coast through to graduation—but it was easier with Mom's help. She'd sat across the kitchen table from him and quizzed him on the first aid questions the test would cover, plus some extra she thought he should know. Probably she was as responsible for saving Una's life as Chris was, if indirectly.

The week before he'd left home for real, he'd spent a couple nights on a familiar trail just outside of Olivine as a test run of his new tent and gear, and Mom had invited herself along.

"Last chance to make sure you'll miss me."

"Mom. Of course I'll miss you."

Chris had been surprised both that she wanted to come and that he wanted her to. Dad had taken him camping many times, but Mom had joined only once that he could remember, when he was in elementary school.

"I backpacked all the way to Azalea when I was your age," she pointed out, defensive. "I had an entire life before becoming your mom, you know."

He'd expected her to nag him about sunscreen and drinking enough water, but she didn't. She'd let him lead, holding her silence while he fumbled his way through cooking on the camp stove and repacked the tent on his own. A look of concern had crossed her face from time to time, but she bit her lip and kept it to herself. She was like Chris, quiet. Dad was the talker.

Maybe she'd just wanted to see for herself whether he really would be okay out there by himself.

On the last night of the trip, Chris had said to her, "I guess you're probably disappointed."

"Disappointed? Honey, I'm always proud of you."

"Yeah, but you don't want me to leave."

"Oh, it's my job to worry." She put an arm around his shoulder and squeezed. "But I've been mentally preparing. I always knew you'd go out and train."

"You did?" He hadn't been sure.

"Yup. And I know you're going to be amazing."

"I got those good genes."

"You've got you. And you're a pretty good one." She gave him another squeeze. "Just don't get yourself killed. I'll be so mad."

"Yeah, that's not in the plan, don't worry."

He should call her, he realized now—it was overdue. But he wouldn't have cell service again until Blackthorn. He hoped she wasn't too worried.

To Una he finally said, "I think she just wants me to come home in one piece."

The fire had gone to coals. Chris prodded them with a stick and added, "Anyway. Thanks for listening. I don't usually talk about this stuff."

Una's expression was difficult to read. "It is good to remember our loved ones. Even if we cannot see or touch them, we can feel them still."

He waited, half-expecting Una might volunteer something about her own family. But she didn't. When the warmth of the fire faded, they got ready to sleep.

Curled towards the tent wall, Chris asked, "Do you really think that's true, what you said the other day about people who've died coming back as pokemon?"

She was quiet for so long he thought maybe she had fallen asleep. "It is what I choose to believe."

—

Una began breaking down the tent the next morning while Chris warmed up with a cup of tea. Already, this had become their routine. He hadn't asked her to do it, but he knew that if he told her she didn't have to, she would anyway.

He walked while he sipped, stretching his legs and checking for any equipment or trash they might have overlooked. A dot of red among yesterday's gray snow caught his eye. Tucked under an overhang, someone had arranged flat rocks into a tower, and on top was an apple cut into beak-sized chunks.

Chris shook his head, smiling, and started to turn back to their camp, but something made him pause.

Kneeling beside the stone pile, he dug into his pocket for a granola bar. He unwrapped it and broke it into small pieces. Not until he was walking away did he notice himself humming, Little bird, little bird ….

Last edited: